Jetons de nécessité – Londres (Royaume-Uni) – Restaurant Audinet

Suivre cette page

Suivre cette pageVoici quelques informations collectées pour le restaurant Audinet et ses propriétaires mais à ce stade nous ne savons pas pour quelle raison le restaurant a fermé. Est-ce volontaire ou bien la clientèle française est rentrée en France ou encore car les autorités ont décidé de suspendre l’activité d’un point de vue politique. Toute information complémentaire que vous pourriez apporter est bienvenue.

Louis Achille Alexandre Audinet, the first owner of the London restaurant named after him, was born c.1806 in Paris. Some time in the early 1850s he was in Belgium, where he married a much younger wife, Marie Elisabeth Petit, following which their first two children, Louise {b.1852} and Achille {b.1854} were born in their mother’s native country. The family then moved from Brussels to London c.1854-56, where they had several more children:

- Eulalie Elisabeth {b.reg.Q2/1856 Strand}

- Marie Adèle {b.reg.Q2/1858 Strand}

- Judith Marie {b.reg.Q3/1860 Lambeth; d.same quarter}

- Alfred {b.reg.Q3/1860 Lambeth; d.Q2/1893 Marylebone}

- Emily {b.reg Q3/1863 Wandsworth; d.Q4/1870 Holborn}

- Alexandre N. {b.reg.Q1/1866 Wandsworth }

- Eliza Alexandrine {b.reg.Q1/1869 Wandsworth}

From the census, below, it seems that the family were not very consistent as to which of their forenames they used.

1861 census at South Lambeth:

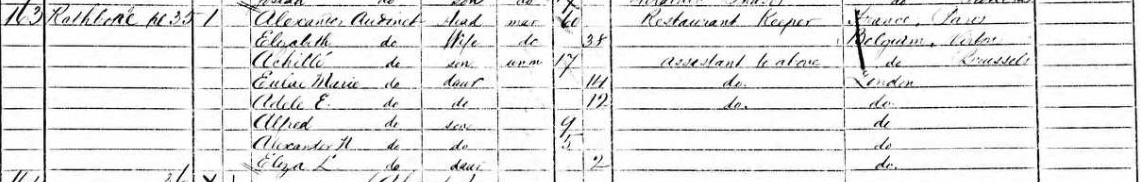

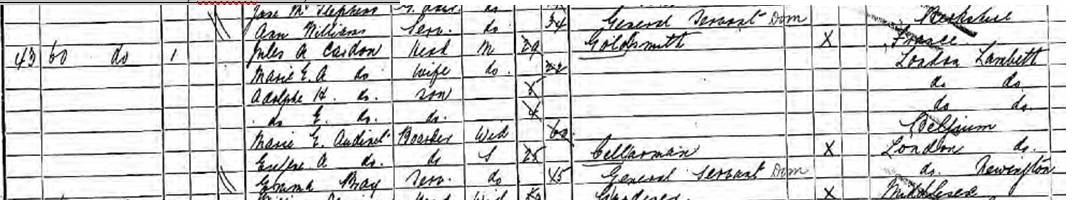

1871 census at 35, Rathbone St, Marylebone:

It would appear that the family moved several times during their early years in London, and that initially M.Audinet snr. was engaged in employment outside the catering industry; for example, in 1861 he was described as a “designer for manufacturer”. Which of these moves represents his first venture into restaurant ownership is uncertain, but the last mentioned, to Marylebone c.1869-71, seems likely; Marylebone is the most central, and Wandsworth the least, of the various areas mentioned.

M.Audinet did not have long to enjoy his new career, however, already in his mid-60s, he died in mid-1872, leaving his 44-year-old wife with seven children aged from twenty down to three. He left no English will; just a restaurant business, which within a few years she developed to become a favoured haunt of Europe’s left-wing political dissidents and artistic elite.

By 1881 Elisabeth had moved within Marylebone, from 35, Rathbone Street to 59, Charlotte Street, with eldest son Achille clearly acting as her right-hand man. In addition to the restaurant, they also had quite a number of lodgers, mostly of French or Belgian extraction.

1881 census at 59, Charlotte St, Marylebone:

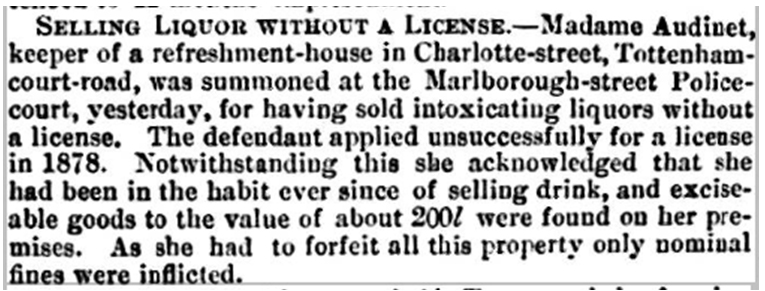

Elisabeth’s “Restaurant Audinet” became to be particularly associated with the French Communards https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris_Commune who occupied Paris from March to May 1870 and many of whom fled to London when they were ousted by the French Army. She was not immune from the ordinary misdemeanours of refreshment house life, as this extract from the Shipping and Mercantile Gazette – Saturday 27 September 1879 shows…..

…however, it is the nature of her clientele which particularly attracts attention. There follow now a few illustrative examples, with their sources, and with references concerning the principal characters which can be pursued if required. More about most of them can be found by simply putting their names into a modern Internet search engine. The story of the society in which Elisabeth moved is summed up briefly in “A small anarchist republic: French anarchists in Fitzrovia” by Nick Heath: https://libcom.org/history/-small-anarchist-republic-french-anarchists-fitzrovia

-:-:-

https://news.glowbox.coop/building-our-commune-exiled-communards-in-britain/ :

“also in Charlotte Street, Elisabeth Audinet ran a restaurant where homecooked French food could be obtained for a reasonable price. “A home of rascals and ruffians,” as one aggrieved French secret police agent put it, Audinet’s was a favoured revolutionary meeting place, and one often frequented by Karl Marx and his Communard sons-in-law, Charles Longuet and Paul Lafargue. Throughout the 1870s, Audinet hosted several banquets celebrating the anniversary of the Commune and she was particularly associated with the Blanquist Communard refugees — she lived with one and another married her daughter.

Following the defeat of the Commune in May 1871, thousands of Communards fled France to avoid deportation, imprisonment, or death. As a result, and due in large part to Britain’s liberal asylum policy at the time, around 3500 refugees (circa 1500 Communards, plus their families) arrived in Britain in the early 1870s. These political exiles made Britain their temporary home, with the vast majority settling in London. Most exiles were relatively young, relatively skilled workers and artisans — jewellers, lace-workers, dressmakers, engineers, mechanics, shoemakers — as well as journalists and teachers.

Despite the hardships of exile, refugee Communards in Britain found an eclectic mix of fellow travellers with whom to share space, ideas and friendships. The places in which Communards gathered — the pubs, the restaurants and the shops — were community centres, places with practical purposes that served newly arriving or struggling refugees. But they were also political places; meeting spots for planning and discussing and making connections.”

-:-:-

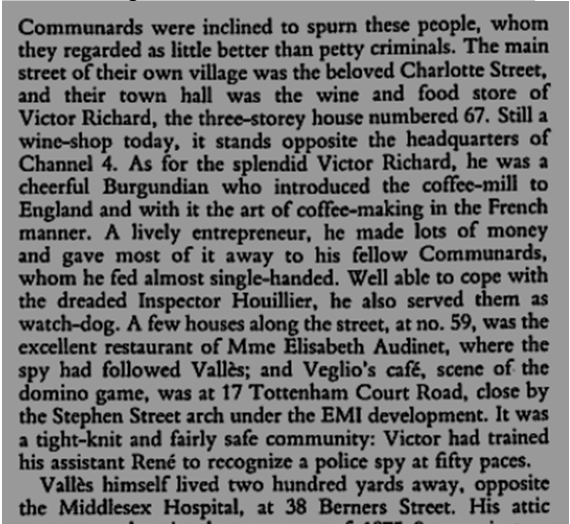

“When the Commune came to Fitzrovia”, by D.Arkell:

{line missing from scan; extract continued below}

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jules_Valles

Inspector Prosper-Isidore Houillier of the Sûreté, or French Secret Police, was allowed to operate against the communards in London with the connivance of his English opposite number in

Special Branch. He features strongly in the article by Nick Heath mentioned above.

-:-:-

Anarchism in Germany: Vol. I: The Early Movement, by Andrew R. Carlson:

“Scheu tells that he and Most often dined together at Madame Audinet, a French restaurant in Charlotte Street, where good meals could be had for a reasonable price. Many of the exiles of the Paris Commune ate there, but the place was also frequented by police spies, some of whom were almost permanent fixtures. According to Scheu, one afternoon Most came into Madame Audinet’s as pale as a ghost and whispered into his ear that his subscription list for Freiheit was missing. Scheu asked him if he suspected anyone.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Most

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andreas_Scheu

-:-:-

Sometimes the Communard story is hidden behind semi-fiction by way of anonymity, as in this example featuring the Audinet establishment which appeared in the “The Demon Duellist” by John Augustus O’Shea, on pages 18-19 of the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News of Saturday 1 January 1881. It is stated that “Hector Achille de Montparnasse” is a pseudonym for a well-known Communard, whom possibly the readership of the day may well have been able to guess.

The British artist Walter Sickert {1860-1942} even painted the restaurant, albeit in miniature, according to http://www.artnet.com/artists/walter-sickert/audinets-restaurant-charlotte-street-and-rosie-EaUZ9h9iBj7jIrHqbzDHeA2

-:-:-:-:-:-

Considering now the history and longevity of Restaurant Audinet after the mid-1880s, it is necessary to see what happened to the Elisabeth’s various children.

Firstly, the sons:

- Achille, Elisabeth’s obvious heir apparent, is shown in the 1891 census as having left his wife Amy and young daughter Louise behind in South London {specifically, 19 Barnwell Road, Brixton} whilst going to set himself up in a new job in Manchester. The 1901 and 1911 censuses show them together at Chorlton-upon-Medlock, which is where Achille died in 1919. In both years he was a hotel cook, but not seemingly running his own premises. Perhaps his love was for food, rather than management.

- Alfred, the cellarman at 59 Charlotte Street in 1881, I cannot find in the 1891 census, but he died young, in 1893, in the Holborn area. He possibly married in the St.Giles area of London in Q2/1890.

- Alexander, the youngest son, was, like his mother, living with his sister Eliza’s family at Brixton in 1891. At 1901 he is in Wood Green, still single; a cellarman in both years, working for I know not whom.

The daughters all married young:

- Louise in 1869, aged 17; details uncertain, as there is some ambiguity as to which of two entries are relevant, but both the potential spouses are French.

- Adèle married in 1874, aged 16, Jules Oswald, who died in 1877 at Eton {circumstances and profession unknown}; and in 1880 Charles Mendes da Costa, a teacher; they may be seen on the bottom of the above 1881 Charlotte St census entry, beneath the lodgers. Charles, a Parisian, was then a teacher. By 1891 they were at 42, Mornington Crescent, Pancras {just slightly to the north} and Charles was a printer & proofreader; and in 1901 a proofreader only, still at the same address. Charles died in 1906 and Adèle in 1907; the former in Guildford Street, near Russell Square.

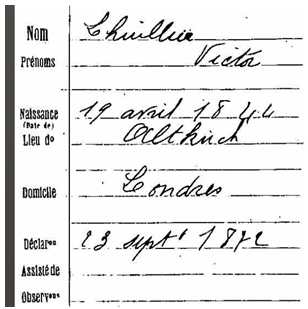

- Eulalie married, aged 18, Victor Lhullier, a French artist and engraver from Alsace, and c.1878-80 they moved away to Hastings, on the south coast of England, with their four young children. Because of the French-German conflict, and Alsace’s particular position in regard to it, Victor found it advisable to opt for French citizenship {rather than German, which was the other option} in 1872, despite already being in London. Widowed at 33 in 1889, Eulalie brought her children back to the old family home at 59, Charlotte St, where she can be found as head of a household which also contained two lodgers, one of them a young French jeweller, but none of her siblings.

- The youngest, Eliza, married Jules Cardon, a French goldsmith, in 1884 when only 15, and the 1891 census shows her mother, retired from business and living with her as a boarder, at Tulse Hill, Brixton in South London suburbia. In 1892 the Cardon’s emigrated to New York, and it may be that they took Mme. Audinet, Marie Elisabeth, with them, for I cannot find her again in the English records. Eliza reputedly died in Manhattan in 1911.

1891 census at 60, Tulse Hill, Brixton:

-:-:-:-:-:-

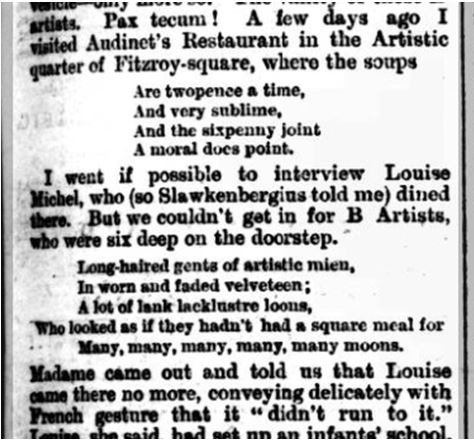

It looks therefore as if the restaurant, if still functioning, moved to a different address or out of the Audinet family’s control. By 1891, 59 Charlotte Street was in use as a private boarding house, run by one Frederick Broadhurst, with not a Frenchman in the household. This, from the Clarion of Saturday 30 April 1892, suggests that the restaurant was still active, and indeed Louise Michel was known to be in c.London 1890-95; { https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louise_Michel }, but the census records do not seem to be consistent with that. Maybe the author of the Clarion article was reminiscing, and talking about past times:

Did the Restaurant Audinet remove itself to Paris sometime in the late 1880s? “La-commémoration-de-la-Commune-de-Paris-à-Châtellerault-1871-1914”, by Charles Alexandre Krauskopf, raises the thought, but it may be just coincidence. It could just be a re-use of the name because of its historic connection with the communard movement:

“C’est dans ces endroits que se retrouvent les socialistes pour fêter le 18 Mars. S’ensuit que, périodiquement, les militants commémorent le souvenir de la Commune à Châtellerault. Ainsi en 1889, 1893 et 1895, c’est au café Audinet, situé boulevard Blossac ou à la Maison du Peuple qu’est fêtée la Commune de Paris.”

The Audinet children seem all to have gone their own various ways, nor have I found any sign, despite the family’s connections, of any of them having fallen seriously foul of the law. Was the restaurant quietly closed down by the authorities, or a deal done whereby they were rewarded in some way for ceasing to act as a dissident hub? One feels that there are a lot of questions left to answer about why such a busy concern faded into apparent obscurity so quickly.

-:-:-:-:-:-

Finally, the token(s). We know that ½d and 6d values exist, and others are likely. From what we know of W.J.Taylor’s activities, and those of the company after his death, the date of manufacture is between 1868 and 1885. Looking at the Audinet family history, I would suggest that the most likely token dates are c.1869-71, when the family first set the restaurant up, or c.1872-73, when Elizsabeth took over the management from her deceased husband.

Ajouter à ma collection

Ajouter à ma collection Vendre/échanger

Vendre/échanger  Rechercher

RechercherValeur : 1/2 penny

Période : 1868-1885

Matière : Laiton

Forme : Rond

Diamètre (mm) : 28,4

Poids (g) : 8,41

Graveur : Taylor

Crédit photo : Collection privée

Ajouter à ma collection

Ajouter à ma collection Vendre/échanger

Vendre/échanger  Rechercher

RechercherValeur : 6 pence

Période : Antérieur à 1885

Matière : Laiton

Forme : Rond

Diamètre (mm) : 28,4

Graveur : Taylor

Références : British Museum MG.784